Etruscan gems

Introduction

Hard-stone gem engraving, on scarabs, begins in Etruria in the second half of the 6th century BC, under the immediate influence of Greek Archaic engraving and probably in the hands of Greek artists. Nuances of style point to Ionian engravers, who were also the earliest in the Greek world. Subjects often follow the Greek, but as in other graecizing Etruscan arts there are special preferences for some subjects, not always treated in the same way, or at all, by the Greeks. Interest in the stories of the Seven against Thebes is an obvious example of this. Etruscan inscriptions, mainly names, appear on many stones. They are transliterations or Etruscan equivalents of Greek names and we may sometimes query whether some were chosen for their appeal rather than their specific appropriateness. Greek myth iconography was readily adopted by Etruscans but not always completely understood, or it is given a somewhat different narrative. There is little which seems to reflect purely Etruscan subjects rather than derived Greek.

The material is exclusively dark red cornelian, so uniform as to suggest that the stones had been treated for this effect, where Greek cornelians are in various shades and many other stone types are used. The shape is invariably the scarab, with a late interest in flat ringstones also. The scarab backs are far more carefully worked than most Greek, a speciality being a patterned upright border or plinth to each stone; some have relief figures on their backs, like cameos. They are treated more as jewellery and often given elaborate gold settings; their use for sealing is not attested. Many are extremely small - little over 10mm long.

The styles to the end of the 5th century BC are close to the Greek but the Archaic tends to linger. At their best they are as good as any Greek, especially the anatomical studies of heroes. In the 4th century BC the a globolo style begins - rendering figures mainly with the drill, in assemblages of blobs. This style soon becomes dominant and even more simplified with animal studies. Finer engraving tends to be reserved for ringstones. There are no signatures but hands can be detected in the earlier scarabs by style, and names assigned [several have been distinguished by Ruth Glynn in an unpublished Oxford thesis (1981) and are used here, with her permission].

Two distinctive groups of metal finger rings (usually gold) are reserved for the end of this section. The first is mainly earlier than the stone scarabs, and is heavily Phoenicianizing, some are in relief; the second is Graecising classsical, all in relief.

Abbreviations used in this section:

AFRings - J. Boardman, Archaic Finger Rings, in Antike Kunst 10 (1967) 3-28.

AGGems - J. Boardman, Archaic Greek Gems (1968).

GGFR - J. Boardman, Greek Gems and Finger Rings (1970, 2001) esp. pp. 152-3.

LHG - J.D. Beazley, The Lewes House Gems (1920, 2003).

Martini - W. Martini, Die etruskische Ringsteinglyptik (1971).

Zazoff - P. Zazoff, Etruskische Skarabäen (1968). see also - I. Krauskopf, Heroen, Götter und Dämonen auf etruskischen Skarabäen (1995).

Master of Boston Dionysos

The earliest personality, working mainly in the last quarter of the 6th century BC. His rather dumpy figures may reflect Anaolian/Ionian styles which also appear in Etruscan relief sculpture. His name piece has an elaborate relief back and he favours multi-figure narrative groups.

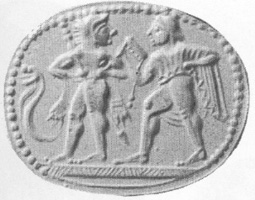

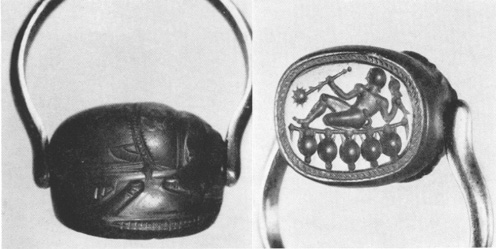

A relief figure of Dionysos on the scarab back. Herakles grapples with a small man (possibly Geras - Old Age) watched by Athena and a woman.

Boston 21.1197; LHG no. 35ter. 14mm. AGGems no. 77; GGFR pl. 408.

Achilles arms, watched by Hephaistos (with crippled feet) holding his shield for him, and his mother Thetis.

Malibu, Getty Museum 81.AN.76.121. 13mm. GGFR pl. 1033.

Achilles? arming, with his new helmet, spear, shield and sword. The added floral is an Etruscan touch.

Florence, Mus.Arch. 15260. 12mm. Zazoff, no.16.

Related to the Boston Master. Herakles quarrels with Apollo over the tripod.

Boston 27.668; LHG no. 14. 12mm.

Mythological scenes

The selection here is of the latest 6th and 5th centuries BC. The subjects derive from Greek myth, sometimes treated in a novel manner and often labelled with Etruscan equivalents to Greek names.

Ajax carries the dead body of Achilles. (The back of the scarab is carved with a frontal sphinx.) Early 5th cent.

Florence, Mus.Arch. 15258. 14mm. Zazoff, no. 11

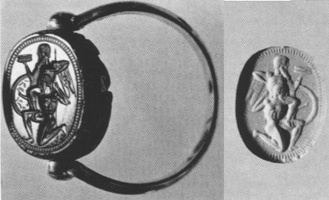

Herakles strikes down Kyknos, child of Ares. Inscribed HERKLE, KVKNE. Mid-5th cent. The Kyknos Master [Glynn].

London, Walters 621. 14.5mm. Zazoff, no. 40.

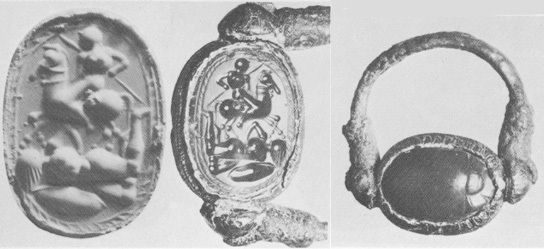

A thunderbolt strikes down Kapaneus, one of the Seven against Thebes. A more popular subject in Etruria than Greece. The scarab back is carved with a squatting African in relief. The same artist as the last.

London, Walters 652. 13mm. Zazoff, no.63.

Aeneas carries his father Anchises, holding the sacred objects, from Troy. Mid-5th cent.

Paris, Cab.Med., de Luynes 276. 13mm. Zazoff, no.44.

Ajax about to commit suicide by falling on his sword. About 450-425 BC. By the Master of the London Athlete [Glynn].

Boston 27.717. 13mm. Zazoff, no.335.

Sleep and Death carry the body of Memnon from the field at Troy. A popular motif. Mid-5th cent.

Boston 21.1200; LHG no.38. 15mm.

Herakles is rescuing Deianeira, who carries his club for him. Inscribed TVRAN (Etruscan Aphrodite). About 450-425 BC. By the Master of the Florence Herakles and Deianeira [Glynn].

Florence, Mus.Arch. 15257. 14mm. Zazoff no.45.

Perseus decapitates the Gorgon Medusa. About 450-425 BC. By the Berlin Master [Glynn].

London, Walters 623. 16mm. Zazoff, no.55.

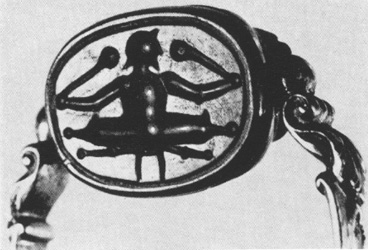

Five heroes. The composition relates to Greek scenes of the Mission at Achilles at Troy, but the figures are given names of five of the Seven against Thebes, a popular subject in Etruria: PARTHENAPAES (Parthenopaios), AMPHIARE (Amphiaraos), PHULNIKE (Polyneikes), ATRESTHE (Adrastos), TUTE (Tydeus).

Berlin FG 194. 16.3mm. Zazoff, no.54.

Herakles holds the sail of his raft (and his bow and arrows, his club beside him), supported by empty wine jars. An subject unknown to Greek art. About 450 BC.

Boston 21.1202; LHG no. 42. 13.5mm.

Warriors, athletes and other figure studies

Many of these are basically anatomical studies based on late archaic Greek figures, variously identified, if at all. They show that the Etruscan engraver was devoted to anatomical patterning well into the later 5th century, a trait apparent in other Etruscan arts.

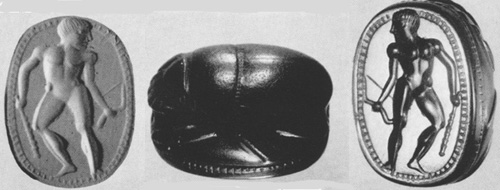

Chalcedony - a cut scarab? - unusual material and shape, but despite the very Greek appearance of the figure, probably of Etruscan make - (Master of the London Athlete- Glynn). An athlete with strigil, oil bottle before him, discus hanging behind. Early 5th cent.

London Walters 490. AGGems no. 340.

An athlete scraping his leg with a strigil. TUTE (Tydesu) By the Berlin Master [Glynn]. Early 5th cent.

Berlin FG no. 195. 14mm. Zazoff, no. 60.

Agate. A youth lifting a cloth from his helmet. ACHILE (Achilles). About 475-50.

Boston 27.720; LHG no. 39. 13mm.

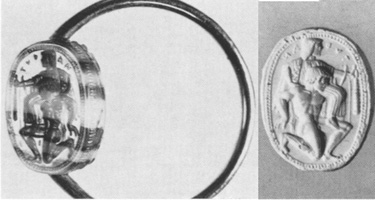

An athlete kneeling on sand and pouring some over his thigh, by the Lewes House Master [Glynn]. About 475-450 BC.

Boston 21.1201; LHG no. 40. 12.5mm.

A collapsing warrior, a broken spear stuck in his shield. Early 5th cent.

Péronne, Danicourt Coll. 14mm.

A satyr dancing holding pipes, a cup and wreath below; totally classicizing. 4th cent.

Cambridge S7, Cat. no. 102. 12.5mm.

A globolo

The name refers to the technique which relies sometimes exclusively, on use of a rounded cutting tip which creates spheroid elements from which the figures are composed. It probably started as a convenient shortcut to making body masses, even in the 5th century but becomes the main technique and dictates style in the 4th century and later.

Incipient a globolo in the 5th century for a study of Herakles with club and bow.

Geneva 1962.19782. 15mm. Zazoff, no. 159.

A satyr on a raft supported by wine jars, holding a thyrsos and a dolphin. A parody of Herakles on his raft (see above, Myth Scenes 10). 4th cent.

Vienna IXB 203. 14mm. Zazoff, no. 228.

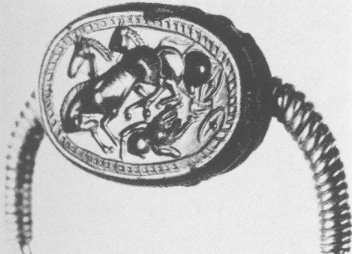

A horseman rides over a fallen warrior, from Campania (Gaeta). 4th cent.

Oxford Pr. 282. 16mm. Oxford Cat. no. 260.

Phaethon falling from his collapsing chariot. 4th/3rd cent.

Paris, Cab.Med., de Luynes 261. 16mm. Zazoff, no. 269.

Ringstones

These are mainly the products of the 3rd to early 1st centuries BC and represent a more realistic, hellenising, style beside the purely Etruscan a globolo scarabs. The subjects sometimes reflect the scarab tradition, but also the Greek Hellenistic, as it is appearing at the time in Roman Republican gem-engraving, and there are Latin inscriptions on some. Stones with cross-banding are often chosen, a fashion in late centuries BC in Italy, and the old hatched borders.

Prometheus fashions a man from clay. Inscribed in Latin, EROS.

Geneva Duval 7234. 14mm. Martini, no. 116.

Archaic gold rings

These are all of the Phoenician cartouche shape, usually in silver, often gilt, but fragile and hardly useful for sealing purposes. The common scheme, of presenting subjects in registers, is of Phoenician inspiration, as is much of the subject matter, with no little Greek as well. The style closely matches that of much other Etruscan orientalizing and 6th-century art of the period before the beginning of scarab production - notably wall and vase painting. The bezels are between 12 and 20mm long.

Panels with a siren, hippocamp, winged lion with snake tail, a siren. Gold.

London, Rings no. 20. AFRings BI31.

A fountain with lion-head spout attended by three figures, with a ape sitting on the fountain. Gold.

Paris, Louvre BJ 1075. AFRings BII2.

The Fortnum Group

These are all finger rings with relief bezels, datable in the second half of the fifth century BC and bearing broadly classical subjects owing much to the contemporary classicising arts of Etruria. They are discussed in J. Boardman, 'Etruscan and South Italian Finger Rings in Oxford', Papers of the British School at Rome 34 (1966) 1-17, to which the following 'Fortnum' numbers refer. The bezels, usually hollow, are 20 to 25mm in length.